Passover has always been one of my favorite Jewish holidays. I remember going to my Bubbie’s (grandmother’s) house as a kid, and looking forward to eating the smorgasboard of sugary treats that she would have—my favorites were the red and yellow, candied half fruit slices.

They were sort of like sour bears in the shape of fruit slices, before I even knew from such a thing as sourbears. As I grew older, the seder moved from Bubbie’s house to my parents’, and I have fond memories of my father leading us through the famed Maxwell House Haggadah, and my mother making all the tasty seder treats: brisket with potatoes and carrots, matzah ball soup, gefilte fish with beet-red horseradish, meatballs in sweet and sour sauce, potato kugel, asparagus, and more kosher-for-passover cakes and treats than any one should consider indulging in a single evening: Streits’ macaroons, chocolate-covered-cherry-gels (they’re better than they sound I promise), honey cake, cinnamon coffee cake, egg kichels, chocolate-covered matzah, chocolate-covered orange peels. Of course the meal would not be complete without the dozens of hard-boiled eggs my Bubbie would make and bring with her. Needless to say, for me Passover has always been about the food, or the lack of some foods (leavened bread and all its delicious derivatives—pizza, pasta, and at one point peanuts), and of course, the stories—the serious thinking about what it means to be enslaved or no longer enslaved and the responsibilities of being a “free people.” As it was explained to me as a kid, the whole reason you don’t eat bread is because the Israelites were in a hurry to escape from Pharoah, and they didn’t have time to let the bread rise, and so we eat the matzah both to remind us of the pain we endured as enslaved Israelites in Egypt and of the rapidity of the Israelites’ exodus. As Jewish people make their way through the Haggadah, we retell the whole story in a ritualized fashion replete with a minimum of four cups of wine, and one of the last things we say before concluding the meal is “Next Year in Jerusalem.” This year I had a chance to fulfill that aspiration.

Passover is a fun(ny) time in Israel in general, and Jerusalem specifically. In the weeks leading up to it, you can see the city undergo a radical transformation. It begins slowly, first signaled by shifts in the shuk. First, the crops of fresh garlic that begin to appear everywhere . At some seders, usually those of Iraqi or Persian Jews, participants literally “whip” each other with scallions, leaks, or garlic to remind themselves and others of the bitterness and hardship of slavery.

[Photo taken by me at Machne Yehudah, the Jerusalem Shuk]

The seder plades, and matzah covers that are prominently displayed

[From right top to left, seder plates, and below matzah coverings, shop on Agrippas at Machne Yehudah, the sign in the middle says "sale of chametz"]

the wishes for a happy holiday, noted by the greeting “chag kasher v’sameach”, literally, may you have a kosher and happy holiday, a greeting which reminds you of the utter importance of observing special rules with respect to food and eating:

[Chag Pesach Kasher v'Sameach from the Jerusalem Tower Electronics shop, with a Na, Na, Nahman poster below]

and the evidence of Passover cleaning—

[Caption/Translation—“This store is Kosher for Passover, please do not bring in any chametz. Thanks, the Managment”]

What is chametz, you may wonder? Good question. And like most things in Judaism, the answer depends on who you ask. Technically, chametz is anything that is not Kosher for Passover. Typically, and both Ashkenazim and Sephardim tend to agree on at least this point, it is defined as any of the five grains—wheat, rye, barley, oats, or spelt, which when combined with water, ferment and can be used to make bread. The word itself derives from Arabic and Aramaic words that mean sour and are associated with the tastes resulting from fermentation. Of course, what is forbidden based on the law (halacha) and what is forbidden based on tradition (minhag) is hotly debated, especially among Jews from different lands. Ashkenazim or Jews from Central and Eastern Europe do not eat kitniot, literally “little seeds” or legumes, whereas Sephardim (Jews of Spanish/Portugese descent) and Mizrachim (Jews of Eastern descent) do. Most of the latter groupings simply do not observe the ban of kitniot. Like the custom of whether or not to eat kitniot, the definition of kitniot itself invites rancorous debate. Usually things like corn, beans, rice, and legumes are considered kitniot, but each community has its own traditions. Needless to say the hekshers (or signs denoting that a food item is kosher and according to whose ruling) differentiate between the two different types of Kosher for Passover— for those who do eat kitniot (l’ochlai kitniot) and those who do not, as indicated by this sign from a the Asian restaurant up the street from us

[Translation: Kosher for Passover for those who follow Mehadrin, for those who don't eat kitniot, and for those who don't eat ]

and this sign for Ben’N’Jerrys, thankfully kasher and “without kitniot”

During Passover, or Pesach as it’s called in Hebrew, things can get a little nutty as observant Jews aim to rid their homes of all chametz, since you are not allowed to either eat, own, or benefit/derive pleasure from chametz during the 8 day holiday. As demonstrated by the signs above, the week(s) leading up to the festival involve a lot of cleaning and purging, of all chametz at the very least. The questions of what constitutes chametz and whose customs do you follow in a mixed Ashkenazi-Sephardi household litter the pages of religious newsletters and some newspapers, a veritable “dear abbey column” of people writing in to Rabbis asking for advice. One of the surprising things I learned from reading such columns was that some cleaning wipes are not kosher for Passover. Why? Because the cleaning solvent used in them may be derived from a distilling process involving alcohol made from chametz, and even though you’re not heaven-forbid eating the cleaning wipes, you are also forbidden from deriving pleasure from them (and the cleanliness they impart?).

If you walk through the more religious neighborhoods (Mea Shearim or Nachlaot for example), you can see the ashen remains of burnt chametz in the streets, as people “liberate” their homes from the faintest trace of the forbidden foods. Some have even been known to get down on all fours, and take a blow torch to the remaining remnants just to be on the safe side. Once the house is clean and ready, they don’t bring any new chametz into the house for fear it might mix and contaminate the Passover food. To be sure that no food comes in contact with unseen, nano-chametz particles, many people will also cover their countertops with plastic table cloths, or tin-foil. We were no exception.

Although the photo is a bit out of focus,you get the idea...

You are permitted to keep some chametz in the house or in your store, as long as it is not “yours” and as long as it is covered up, out of site, and completely separate from anything that is kosher for Passover. Consequently, many Jewish people “sell” chametz to a non-Jewish person (presumably to be bought back after the holiday). Young boys wandered the market with signs saying they were either selling or buying chametz (see the sign nuzzled in between seder plates in the photo above).

As the week preceding the holiday wore on, the city began to transform. The shops slowly entered a zombie-like state, with the chametz getting covered up with butcher paper, and thus put out of sight, or with the shelves emptied of chametz altogether. We noticed lights turning off and on in apartments which had appeared vacant just days before, as tourists poured in from around the world. The city, like the spring itself, seemed to be bursting with a kind of fullness, and frenetic energy as everyone prepared for the climax of the seder, the ritual dinner which begins the holiday and recounts the story of the Jewish people being freed from Egyptian slavery.

[These were the crowds in Mamila the other day]

Part of the requirements for the seder, are that you open your home to guests, you recline while you eat, and that you retell the story of slavery and the freedom from it following 15 prescribed steps. The word seder literally means "order" in Hebrew, and with 15 steps which are sung in order before each step is completed, it's hard to get off track. There are several customs which suggest you should extend the seder as long as possible, and in Jerusalem people often greet each other the day after with "How long did yours go?" and "What time did you eat?" We were fortunate enough to be invited to a friend’s parents house for seder, and were treated not only to a wonderful feast, but also to an engaging and insightful recounting which lasted from 7:30pm to nearly 2 am, with the meal finally taking place some time around 10:30 pm. Since Passover coincided with Shabbat this year it was even more festive. Luckily we arrived before sundown, and I was able to snap this shot before the holiday restrictions set in.

[Seder table. Notice each chair has a pillow, the better to recline with, and the seder plate with all the requisite parts was featured prominently in the table's center, to its right you can see the mountain of charoset --symbolic mortar for the bricks the slaves used to build the pyramids--shaped into a pyramid itself.]

One of the fabulous things about Passover in Israel is how much it is part of the fabric of daily life. Rather than being the exception, here it is the rule. Schools and shops close down, and the whole populace is on vacation. Observing the holiday itself is a bit complicated, as the first 2 and last two days are “chag” much like Shabbat when no work or cooking is done, stores close early, and a peaceful tranquility descends upon the cities. The part in the middle is called “chol ha-moed”, and the cities come alive with events for children, festivals, live music. It’s like the whole country (or at least the Jewish parts) are celebrating the symbolic freedom from slavery by picnicing, barbequeing, hiking, going to the parks and beaches.

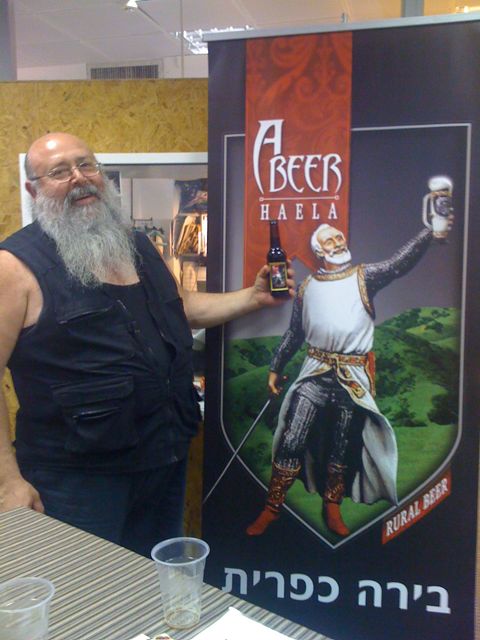

Part of what I find so delightful is that it is taken for granted. For example, the week before, we attended a fantastic beer-tasting (something that deserves a post in itself, given that micorbrew culture has only begun to catch on in Israel within the last few years).

A bunch of micro-brewers had gotten together to sell off what was left of their product before the holiday. It was a lovely event, held in a two-level building that houses many artist studios, sandwiched between the shuk and the art school Bezalel. There were a number of different vendors, some were more familiar like the Jerusalem-based Shapiro beer, and others which were much smaller and independent. But the whole premise behind the scheduling was that they were going to get rid of the beer before Passover.

Beer Bar above and Village Beer below, the brewer for Village Beer also made amazingly tasty and hand-crafted kosher chorizo sausages, two things I never thought I'd see go together!

The newspapers included special sections with holiday recipes, and articles on the newest haggadahs. One which garnered a lot of attention was Jonathan Safran-Foer and Nathan Englander’s New American Haggadah, which was featured prominently in Haaretz's weekend insert last week. We actually got to see it in person as two copies made their way to our Seder here in Jerusalem.

Secret matzah bakeries popped out of the blue...

We stumbled upon this one on the way to shuk. Of course, since they hand roll each matzah every 18 minutes, you can imagine how long the line was.

In Israel, we can assume that whatever is on the shelves in the stores during the holiday is kosher for Passover (at least for someone), and we can even eat out at restaurants during the holiday itself. For me this is the biggest source of pleasure of “this year in Jerusalem,” for it is the thing I tend to miss most while celebrating in the States.

In the U.S., Passover is a time when I feel my separateness as an observant Jew most definitively because I “keep Passover,” which means I don’t go out to eat, I bring matzah sandwiches to school, and for the 8 days of the holiday I am, very noticeably different. As a university professor, I generally mingle with a variety of people both at work and socially, and so to be so noticeably separated by the choices I’m making about what I eat is to recognize three times a day that I’m different. While it’s true, I also keep kosher year-roudn and there is a certain degree of separateness that comes with eating because of it, there is something unique to the separateness of Passover. There’s something about literally “breaking bread” with folks, that makes you realize all of a sudden and very viscerally –you’re not one of “the” folks because you’re not eating the bread. And of course, my colleagues always seem to be eating things that are way more tantalizing and tasty than the matzah and avocado sandwiches I tend to bring.

In Israel, there is almost the opposite problem. There are so many options!

Cakes galore!!! Not the red lettering in the sign indicating they are, you got it, Kosher for Passover.

Fear not if you prefer cookies....

Usually there is a bit of dread which accompanies the onslaught of Passover sweets, because they all end up tasting more or less the same by the end of the week, but here in Israel, there are a plethora of options, more so if you continue to eat kitniot.

As I walked through Mamila, the new urban shopping center which borders the old city,

I gently elbowed my way through the swarms of tourists to the bakery Roladin, which is known to produce some of the best Passover treats.

They did not disasppoint, as I ate a piece of kosher-for-passover Pizza that was as good, and arguably better than most of the pizza I’ve had in Israel thus far.

The crust was both soft and crispy, not like the matzah pizza (which inevitably got soggy), that I remember from my youth. In fact this pizza was so good, I felt a little guilty eating it, as part of my strongest memories of the holiday, are of feeling a little bit deprived so you remember the “taste” of slavery. Clearly, I’m not alone in this sentiment, as Gabriella Gershensen’s take on Passover treats in the States also underscores this feeling.

Of course that guilt did not keep me from buying the more traditional macaroons, though these were dipped in merengue. They were so light and delicious I felt I was eating sweet little clouds of air.

And how could I resist some KP tiramisu.

Clearly, Jim and I were so anxious to try the latter, that we couldn’t hold back long enough to take a picture before digging in.

As I walked through the midrichov, (pedestrian mall) downtown, I was delightfully surprised to see Max Brenner's chocolate shop selling kosher for Passover crepes. Crepes!! Surely that was cheating, or at least it felt that way. There seemed to be something mischievous in eating all the regular things made KP through some magical alchemy of substituting kosher for Passover ingredients for the chametz. Last night, I even went to a pasta restaurant where all the dishes were made with special pasta made from matzah meal, so even those who don’t eat kitniot could eat there.

Of course, here I was delighting in what it feels like to be part of the majority, while some of the friends we’ve gotten to know through the Fulbright program were having the opposite experience. To read an insightful piece on what it’s like to be part of the Christian minority in Jerusalem during Pesach, read Hilary Mead’s eloquent post. And to see some wonderful photos of Easter in Jerusalem, see Terence Gilhenny’s post.

Ah Jerusalem, so full of wonder, beauty, and contradictions. Of course, I wouldn’t have done my duty in talking about Passover if I hadn’t in some way retold the story, so I’ll end this post, with a lovely interpretative Salsa dance that reenacts the whole Passover Haggadah in a Salsa-dancing-flash-mob form in the middle of Paris! Thanks to David El Shatran and the JewSalsa studio in Paris for sharing this. Can you imagine what the local the Parisians must have thought? This night is sure different from all other nights...or at least this moment!